The Battle of Hudson Bay Project 1697

In September, 1697 Captain Pierre Le Moyne D’Iberville, a Canadian by birth born to French parents from Normandy (he was of Viking descent), and his ship The Pélican were anchored at Port Nelson in Hudson Bay. He had sailed with a fleet of warships to disrupt and destroy the British presence in the Canadian North. The Pélican was a 3rd rate man of war 44-gun 200 foot frigate with a battle tested crew of 150 sailors.

Before the battle, the Pélican became separated from the rest of the French squadron in heavy fog, but D’Iberville elected to forge ahead. This set the stage for a little-known but spectacular single-ship action against heavy odds. As the Pélican sailed south into clearer weather, she approached the trading post of York Factory, and a group of soldiers went ashore to scout out the fort. Captain D’Iberville remained on board the Pélican. While the shore party was scouting the fort, D’Iberville saw the sails and masts of approaching ships. Thinking the rest of his squadron had arrived, he set off to meet them. D’Iberville realized that the ships were not French, but were, instead, an English squadron when one fired a shot across the bow of the Pélican.

The English squadron comprised the Royal Navy warship Hampshire under Captain Fletcher, mounting 50 guns, the Hudson Bay Company’s Hudson’s Bay (200 t) commanded by Capt. Nicholas Smithsend and mounting 32 guns, and the Hudson Bay Company’s Dering (260 t) commanded by Capt. Michael Grimington mounting 36 guns.

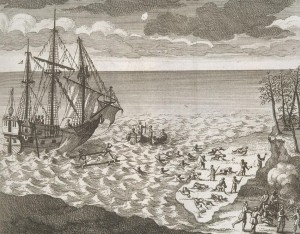

D’Iberville, his shore party out of reach, elected to give battle. The battle began as a running fight, but after two and a half hours, D’Iberville closed with the English and a brutal broadside-to-broadside engagement took place between the Pélican and the Hampshire. The English seemed to be gaining the upper hand with blood running from the scuppers of the Pélican into the water. Captain Fletcher demanded that D’Iberville surrender, but D’Iberville refused. Fletcher is reported to have raised a glass of wine to toast D’Iberville’s bravery when the next broadside from the Pélican detonated the Hampshire’s powder magazine. The Hampshire exploded and sank.

The Hudson’s Bay and the Dering seem to have played only a limited supporting role in the final stage of the engagement. The Hudson’s Bay was damaged and struck its colors to Pélican after theHampshire blew up. Dering broke off the engagement and fled, but the Pélican was too badly damaged to pursue.

The Pélican was also fatally damaged in the battle. Holed below the waterline, the Pélican was grounded as close to the shore as possible and D’Iberville got his sailors off the ship. He also removed several cannon and marched to capture the Hudson Bay Company trading post at York Factory. The arrival of the remainder of the French squadron shortly thereafter led to the surrender of York Factory on September 13, 1697.

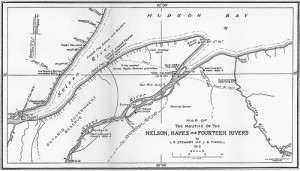

The Hudson Bay employees captured at York Factory include the Henry Kelsey who was the first European to set foot on the prairies of North America and see bison. Journals kept by York Factory employees record the locations and events of the Battle of Hudson Bay. Naval and Hudson Bay maps also record landmarks and data points that show where the battle occurred.

Captain D’Iberville went on to found Biloxi, Mississippi and find the source of the Mississippi River. He was responsible for the creation of the French settlements in Louisiana and finally died in Cuba, on July 9th 1706, of yellow fever. He was 7 days short of his 45th birthday. This is the story of one of the most influential persons to live in North America before the founding of Canada or the United States.

Captain D’Iberville went on to found Biloxi, Mississippi and find the source of the Mississippi River. He was responsible for the creation of the French settlements in Louisiana and finally died in Cuba, on July 9th 1706, of yellow fever. He was 7 days short of his 45th birthday. This is the story of one of the most influential persons to live in North America before the founding of Canada or the United States.

We have an advisory board that includes a Director of The Explorers Club that sailed with Thor Heyerdahl (Capt Norm Baker), a world class film director to help tell the story (Guy Maddin), experts in archaeology and history and an experienced exploration crew. The full knowledge and ability of The Explorers Club is helping.

The Expedition

From the York Factory area we will conduct both land and sea searches for Le Pelican, the Hampshire, and the Hudson’s Bay. Le Pelican and the Hudson’s Bay are likely on dry land due to isostatic rebound and changing topography. Isostatic rebound is an effect where the land is slowly rising from the position it sank due to the weight of the mile thick glaciers of the last ice age.

With over 100 cannons and the vessels being over 100 feet long we are searching for metal and general debris. Hudson Bay is less than 100 feet deep where the ships sank and there is a sandy bottom. There is a strong current and Hudson Bay is scoured by ice each winter. We will use side scan sonar to help us map and search the bottom of the Bay. We will dive at Five Fathom Hole to evaluate the data collected via magnetometer, side scan sonar, and diving on a location used for over 300 years as the anchor site for York Fort. We will turn over all of our data to the Government of Canada and Manitoba for future expeditions.

What are the objectives and phases?

We have a two-stage mission:

1. Electronic underwater survey to identify the wreck of the HMS Hampshire – We have an excellent international team of commercial underwater survey experts, maritime archaeologists, and underwater recovery experts whose mission is artifact retrieval and conservation. Our primary goal is to identify the location of the HMS Hampshire. Using advanced technology we will survey the bottom of Hudson Bay and create a data package for analysis and identification of the location of the HMS Hampshire. We are currently proposing a private/public partnership with Parks Canada, the Canadian War Museum, and the Royal Canadian Geographical Society so that the Fara Heim team can operate with proper permits and complete transparency with the Canadian government.

2. Underwater archaeological activity – Once the Hampshire is identified a plan will be put together based on the requirements of the Canadian and UK governments. The Hampshire was sunk with all hands lost and is a gravesite. The vessel is also an untouched archaeological historical site. Any underwater archaeological activity will only be completed within the constraints of a mutually agreed upon plan. If there are no funds to recover and preserve artifacts the only activity may be to create a national historical site to protect the wreck of the Hampshire and leave it for nature to return to the elements.